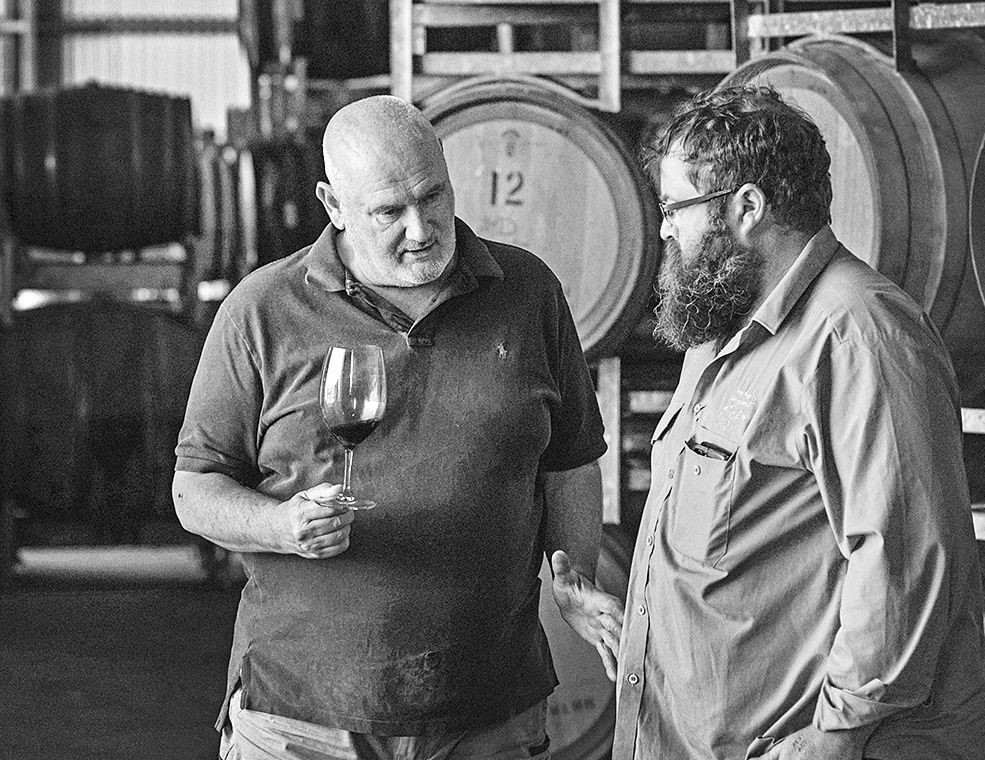

Hedonism Meets... Chris Ringland

Chris has been crafting critically acclaimed Barossa Valley wines for 30 years. Tiny releases of world-beating Shiraz made a name for Chris in the 1990s, but he has since garnered acclaim as the flying winemaker for top Spanish winery Bodegas El Nido, making not one, but two of the Jumilla's finest reds. We caught up with Chris in the midst of the Australian winter to talk about life in the vines, making wine during the pandemic and working in a pickle factory...

Thanks for taking the time to talk to us Chris. How is the 2020 panning out?

We’re approaching mid-winter here and it’s a bit unsettling for me. I’m normally in Spain at this time of year, attending to the blend planning for Bodegas El Nido and Bodegas Alto Moncayo. This is the 19th year of my Spanish winemaking collaboration. I miss the escape from what passes for winter in Southern Australia to the balmy early days of Summer in Spain; that first ice cold beer in my favourite bar at Porta de Atocha before boarding the AVE high-speed rail to Alicante.

I’m doing the 2018 Spain blends at home this year. 180 bottles of samples from El Nido were sent by air. I completed the plan last week and signed off with the crew in Jumilla by teleconference. The samples from Alto Moncayo 2018 are in transit. I’ll work on those blends early next month.

As you know, the build up to vintage 2020 in Southern Australia was very complicated. We have experienced a run of dry winters and drought conditions in the Barossa since 2017. Grape yields have been unusually low for the past two vintages. Fortunately, despite difficult, dry conditions during Spring, weather conditions during mid-late Summer for 2019 and 2020 have been very benign, with mild and even temperatures and cold nights resulting in very favourable ripening and fruit composition.

The anxiety and stress resulting from the bush fires in the Adelaide Hills, Kangaroo Island, Southern Victoria and New South Wales made it difficult to be optimistic about the coming vintage in 2020. Fortunately for the Barossa, the prevailing winds directed smoke away from the region.

An unusual run of cold nights and mild days during February and March created perfect environmental conditions for the ripening of the albeit small yields of grapes. The outcome for both reds and whites is very encouraging. I have tasted some excellent early bottled Eden Valley Rieslings and the intensity and richness of Cabernet and Shiraz is outstanding. Grenache and Mataro have also come out strong. These have the potential to be long-lived wines.

"It may be unfashionable, but I like to make red wines that are capable of ageing gracefully for several decades"

I read that you started your winemaking career quite young, making wine using grapes from a neighbours vineyard – can you tell us a little about what got you into wine and what you learned from those early winemaking experiences?

I started winemaking as a school holiday project when I was 14. Back yard table grapes were a very popular garden fruit tree in New Zealand when I was a kid. We had our own vines and most neighbours around in our semi-rural suburban South Auckland block did as well. Most years people had far too many grapes to handle.

I found an old book called Peggy Hutchinson’s Home Made Wine Secrets. This book was very popular in the UK post-WW2, as many Brits got into home winemaking to fill the breach created by the disruption of the European wine business. I’m sure you know that making wine at home using tinned grape must concentrate was very popular in the UK in the 1960s. The book was a very straightforward instruction manual on basic winemaking with recipes for all types of fruit wines, cider, perry and mead. I coaxed some schoolmates into helping me and we did deals with the neighbours to harvest their grapes in the promise of finished bottled wine in return. I set up a small winery in the basement of my parents house.

Our home winemaking experiments worked out very well. The process of fermentation was very interesting; the magic of the transformation of sweet juice into wine. My parents, both arrivals from Europe in the 1950s and therefore wine drinkers, were delighted at the appearance of a drinkable home made supply. New Zealand was not recognised for winemaking in the 1960s, they were mostly making beer, "Port" or "Sherry". Dalmatian immigrants changed everything and good locally grown table wine began to emerge in the 1970s.

After graduating from high school in 1977, I applied to the University of South Australia for admission in to the Bachelor of Applied Science Study Degree in Oenology and Viticulture at Roseworthy College. I wrote them an essay about my experiences with home winemaking. I was accepted into the course for the 1979 intake. I did a deal with my parents to match me dollar for dollar on my savings and got a job for a year in a pickle factory and in 1979 I flew to Australia...

I understand you worked some vintages in California in the early part of your career – where did you work and what did you learn from your stint in the USA?

After I graduated from Roseworthy in 1982 I returned to New Zealand to work as an intern winemaker. Unlike a lot of my Roseworthy classmates, who had family wineries to return to, I needed to develop my professional experience independently. The New Zealand wine industry was going through a major transformation in the 1980’s. Disease and phylloxera resistant hybrid grapes, which were easier to grow, but which made pretty ordinary wine, were being replaced with classic European varieties, such as Sauvignon blanc, Chardonnay and Cabernet. It was an exciting time, but I was eager for some international adventure.

In 1986 I secured a cellar hand vintage job back in the Barossa valley and used the income from this to secure vintage work in California, followed by a break with friends, travelling around the UK, and then back to the Barossa in time for the next vintage. The California experience was with Mirassou Vineyards in San Jose. A very old California winery and a great experience, combined with travel to visit wineries in the nearby Santa Cruz mountains, Napa Valley and Sonoma. This was a very exciting time for California wine and an insight into what was about to develop in the South Australian winemaking regions. During the 1970’s the Barossa valley was viewed as somewhat of a past-it winemaking region. Coonawarra, Mclaren Vale and Clare were very much in the spotlight. Victoria, Tasmania and West Australia were coming to the fore. Looking back, it was incredible how the Barossa re-emerged in the 1980’s.

"1996 was such a great vintage that my entire barrel selection was bottled as Three Rivers. It was the first Australian wine to be rated at 100 points by Robert Parker"

Your name is synonymous with Barossa Shiraz – what’s the best thing about making wine in that part of the world and what do you find most challenging?

During a break in the Barossa Valley between California vintages in 1988 I was approached by Robert O’Callaghan to help him with some cellar work with his new project, Rockford Wines. You turn up for work, do your job and one day you discover that you’ve been there 18 years! Robert really taught me how to make red wine. It’s one thing to know the science, but altogether another to learn the practical detail. The Barossa is Shiraz. The climate and geology are a perfect match. The style that I learned at Rockford was gently made in small individual vineyard batches and matured for at least 2 years on seasoned oak. Then, the assembly of the matured batches in a blend for bottling created both a house style ( Basket Press Shiraz ) and a display of the peculiarities of the vintage. During the late 1980’s the reinvigoration of the Barossa saw a big return to interest in fulsome, traditional reds that could age gracefully.

In my view, the biggest ongoing challenge is managing water resources to sustainably grow grapes in an arid environment. The younger generation of vignerons are tackling this from the ground up. There is now much greater understanding about the importance of soil health. A clearer understanding about the impact of agri-chemicals on soil microbiology. Re-charging the soil improves water holding capacity and creates a more balanced nutrient environment for the vine. I’m seeing a parallel development in Spain.

Reading about the origins of Three Rivers and Randall’s Hill, it sounds like it was a long road from purchasing an over-grown old vine Shiraz vineyard to getting it to back to peak condition. Can you talk a little about discovering the vineyard and the work involved with making those legendary early vintages of Three Rivers and Randall’s Hill?

Early on in my time at Rockford, just before vintage 1989, I was offered some Shiraz to make for my own after-hours project. I spoke with Robert O’Callaghan about the possibility and he gave me permission with the provision that the batch of wine could be no more than 1 tonne ( approximately 60 cases of wine ). He didn’t want my sideline project interfering with my day to day at the winery. Rolf Binder negotiated the deal for the grapes. Jane Ferrari came in on the arrangement. We made the little batches of Shiraz from purchased grapes at Rolf’s family winery. I decided to mature the wine in New French oak, to make a clear stylistic distinction from the New American used for top batches at Rockford. By the time the 1989 was ready to bottle late in 1991, Jane had to pull out due to conflict of interest issues. I decided to continue alone. The three rivers label was created and the wine sold to a small group of private customers and retail in Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney.

In 1994 it came to my attention that a small old Shiraz vineyard was for sale in the Barossa Ranges at Flaxman Valley. It was a great location, high in the ranges, but in bad neglect. I was able to purchase the 2 hectare vineyard, plus an adjoining vacant block and a small stone cottage for a very decent price. It took me 5 years to re-work and re-trellis the old vines, but vintages 1995, and 1996 were very good years. The vineyard yielded more grapes than I could use to honour my agreement with Robert, so he readily agreed to purchase the balance for inclusion in the Rockford Shiraz portfolio. So, in 1995 I started fermenting my little batch of Shiraz at Rockford, then moving the finished wine in barrel back to an old insulated tin shed at my Stone Chimney Creek road property. With the 1995, for practical reasons, it was agreed that I could increase my batch size to 2 tonnes ( the vineyard routinely yields between 4-6 tonnes ) and the extra 2 barrels gave me the opportunity of creating a second wine, which I named Randall’s Hill, in acknowledgement of Thomas Randall, the pioneer who had planted the vineyard in 1910.

1996 was such a great vintage that my entire barrel selection was bottled as Three Rivers. This was the first Australian wine to be rated at 100 points by Robert Parker. 1997, in contrast, was entirely allocated to the Randall’s Hill label.

Some of the wines you produce are truly heroic when you look at the specs – your fantastic 2008 Hoffman Shiraz (which I was lucky enough to taste last year) is aged for over five years in new French oak and bottled at 17.5% ABV. How do you go about achieving balance whilst making wines in this big, bold style?

Right from the beginning, during the establishment vintages at Rockford, I noticed that Robert most often deferred to the growers understanding of their vineyards to determine when the grapes were ready to harvest for the 'Basket Press' style. In order to achieve fully evolved, soft tannins and gentle acidity, Shiraz needs to hang on the vine until very ripe in order to have the right composition for long ageing. Early on, as the wines were noticed by critics, I was perplexed by a tendency for some to describe this as over-ripe, as if there was some unspoken reference point that they were using that we weren’t party to. I find the term over-ripe pejorative and somewhat high-handed.

The Hoffmann family, in particular Adrian, my partner in the North Barossa Vintners project, were instrumental in developing this understanding of Shiraz ripeness. We don’t talk about baume or potential alcohol. We talk about the condition of the vines and the flavour in the grapes. Winemaking is very much like cooking; gently coaxing the flavours and tannin components from the grapes at, albeit a very modest temperature and then allowing the self-preserving tincture to evolve in its own way. A chef chooses the ingredients with a specific outcome in mind. For me, fully ripened Shiraz has the flavours and structure to produce both complexity of flavour and longevity. The use of new oak barrels is fundamentally important for red wine of this style. It is a fascinating journey from the evolution of oaken barrels as the first mass-produced storage and transportation vessel for liquids, including wine, to the understanding about the way that certain types of wine evolve and improve by being stored in these wooden vessels. Our understanding about the way that the phenolic compounds of red wine polymerise and stabilise is relatively recent. It all stems from the pioneering work of Edwin Haslam at the Leatherhead Food Research Laboratory in the 1930s.

I was motivated to push the limits of maturation time of my Shiraz in barrel from very early on. My work at Rockford showed me how to look after wines in barrel to reduce the development of volatile acidity, the most problematic limiting factor for maturation time. I have also been strongly influenced by my work in Spain, in gaining an understanding the maturation techniques used to create Gran Riservas. It may be unfashionable, but I like to make red wines that are capable of ageing gracefully for several decades.

"Champagne is very important for maintaining the mental health to cope in these uncertain times..."

Can you tell us a little about working with Adrian Hoffmann on the North Barossa Vintner’s project?

The Hoffmann family started delivering grapes to Rockford in 1992. They had a formidable reputation for growing Shiraz capable of producing wines of the grand style from the Northern Barossa. As I worked with Adrian Hoffmann over the following years I learned to trust his observations and decisions about when his grapes were ready for harvest in a particular vintage. After I departed from Rockford in 2006, to devote more time to my Spanish projects, it was a delightful development to be able to work directly with Adrian on our new winemaking venture.

Alongside making wines in Australia, you also make wines in Spain including Clio and Juan Gil. Can you talk a little about working with Bodegas Juan Gil and what you love about the wines of Jumilla?

I was invited to become involved in the development of the Bodegas El Nido project with the Gil family in 2001. I spent a lot of time inspecting various vineyards with them, both in the winter and again in the spring to see what the potential was. There were some very great old Monastrell vineyards and also some unexpectedly good Cabernet Sauvignon that had been planted in the early 90s. I proposed that we make the wines a separate vineyard batches using the same techniques that I was using in the Barossa, with special emphasis on pressing the ferments off skins using basket presses. I also proposed the use of 100% new American and French oak.

We started making wine in 2002. The results were excellent and I have just completed making the blending plans for Clio and El Nido 2018. It is very rewarding to have developed a winemaking collaboration from Australia to Spain that has gained the recognition and following that it now enjoys. Also, Jumilla was considered a somewhat secondary wine growing region when we started out. Now, I hope thanks to our work together, it has gained a top level reputation.

When you’re not drinking your own wines, which Aussie producers do you turn to for a good bottle of wine?

Because of the connections from winemaking school, I do a bit of swapping with old mates. I try to keep up with Victoria and Tasmania Pinot Noir, but my everyday go-to is either Chardonnay (preferably Chablis) or Eden valley Riesling. Champagne is very important for maintaining the mental health to cope in these uncertain times.

And when you’re not drinking wine, what’s your tipple of choice?

Gin. As W C Fields advised, you have to have something to drink before breakfast. I make my own. I have refurbished an old Inland Revenue Still, which I keep in the kitchen. My favourite botanicals ( apart from Juniper ) are Coriander seed, China black tea and Sichuan pepper.

Below are a few picks of fine Australian Shiraz from Chris and click here to view our full selection.